In 1975, Suriname became independent and many Surinamese came to the Netherlands. Among them also a group of Javanese who themselves or whose parents had been brought to Suriname from the Dutch East Indies as contract workers. A substantial number of these people found shelter in Sint-Michielsgestel. There is now a book about this rather unknown group.

Through Lauran Toorians

It may be assumed that slavery was abolished in the Netherlands in 1863. From July 1, 2023 to July 1, 2024, this will be reflected on in many ways during the Commemoration Year of the History of Slavery. Compared to other countries, the abolition in 1863 came late. The joyful fact did not happen by itself and immediately led to other problems. The slave owners had to be financially compensated for their losses and to prevent work on the many plantations from suddenly coming to a standstill, it was stipulated that although the slaves were now free, they would still have to continue working on ‘their’ plantation for another ten years. As wage workers, but still not completely free to go where they wanted. Replacement workers then had to be found for those plantations and other places where slaves worked until 1863.

Urgently looking for replacement workers

It will not be surprising that freedmen who saw the opportunity to work elsewhere were more than happy to turn their backs on their old owners. The plantation owners, supported by the government (the Ministry of the Colonies), diligently looked for replacement, cheap workers. With the consent of the British government in India, many Indians (Hindustani) were recruited as contract workers, but this had the ‘disadvantage’ that these were British subjects who were therefore not freely available to the Dutch. From 1890 onwards, Javanese were recruited, often in villages in Central and East Java.

The recruitment took place under more or less (to downright) false pretenses. People would go to Suriname temporarily, earn well there with not too hard work and sometimes mountains of gold were promised. Others left voluntarily, seeking adventure, to get away from creditors or troublesome relatives or to marry a loved one who was not accepted by the family. In total, almost thirty-three thousand people from the Dutch East Indies would make the journey. More than a quarter of them eventually returned.

The first group that arrived in Suriname in 1890 consisted of ninety-four people. That experiment was found successful and larger groups were introduced from 1894 onwards. This gave Suriname a Javanese, Muslim population group that – just like Hindustanis – succeeded in retaining its own culture. Although the indentured servants were not slaves, their options were limited and they did not become rich. The latter also prevented many from returning to Java. They were ashamed because they had not become rich. After 1931, there were no more contract workers, but there were still ‘free migrants’.

In the former Beekvliet seminary

Surinamese independence in 1975 made many Surinamese choose Dutch citizenship. They also included Javanese who feared they would be in a pinch between Hindustanis and Creoles. Nearly four hundred mainly older Javanese came to the Netherlands in the weeks before independence. About three hundred of them, mainly seniors with their grandchildren, found shelter in the former Beekvliet seminary in Sint-Michielstel. After a lot of fuss – especially about money – Nieuw Beekvliet retirement village was built in 1988 for the elderly in Sint-Michielsgestel. It closed its doors in 2017, after which the last residents moved to the Wereldhuis in Boxtel.

An Islamic section was set up for these people at the cemetery in Nieuwstraat in Sint-Michielsgestel. The Foundation for the Remembrance of Javanese Immigration (STICHJI) is currently raising money to preserve this unique cemetery and to save a memorial from oblivion.

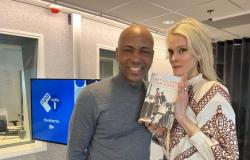

And there is now also a book about this rather forgotten group, written by Sabine Ticheloven. The book is an integral part of the project ‘More than a song’ with which the Javanese Immigration Commemoration Foundation draws attention to the history of the Javanese who were transferred from the Dutch East Indies to Suriname during the Dutch colonial administration. About sixty-five contract workers who were embarked for Suriname between 1918 and 1928 are buried in Sint-Michielsgestel. Fifty-one graves are still visible – the rest have already been cleared – and of these, seventeen are uncovered. The foundation’s aim is to still have those graves bordered and provided with a memorial.

Sabine Ticheloven, Together on Beekvliet. The Javanese Surinamese in Sint-Michielsgestel (1975-2017). Edam: LM Publishers 2024, 128 p., ISBN 9789460229633, hb., € 24.50.

https://stichji.javanen.nl

© Brabant Cultural 2024

Tags: Book forgotten group Javanese Surinamese SintMichielsgestel

-